Bilingual Brilliance: How speaking two languages boosts young minds

Bilingualism is not just a skill, it’s a superpower. It enhances cognitive development, supports academic achievement, fosters creativity, and builds bridges between cultures. As educators, parents, and community members, we have a responsibility to nurture and celebrate bilingualism, not just in policy, but in practice. This is the opinion of Alison Rees Edwards, lecturer in Early Years at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David.

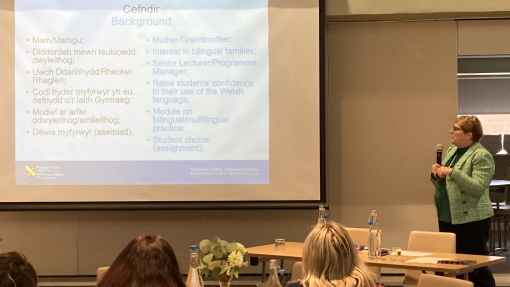

I recently had the pleasure of presenting on the importance of bilingualism at Ceredigion’s Childcare and Play conference, where professionals from across the sector gathered to explore best practices in early years education. At the University of Wales Trinity Saint David (UWTSD), we actively promote and support the Welsh language across our programmes. In our Early Years Education modules, bilingualism is a key theme, and students are encouraged to explore it through flexible assignments that reflect their own experiences and interests. This flexibility often raises student confidence, allowing them to connect theory with practice in meaningful ways.

Let’s begin with a simple question: What does bilingualism mean to you?

Definitions vary depending on who we read, what our experiences are, and even where we live. Some define bilingualism as equal fluency in two languages, while others see it as the ability to communicate effectively in more than one language, regardless of proficiency. These definitions are shaped by cultural, educational, and personal contexts.

One particularly useful author in this field is Colin Baker, who introduced the concepts of simultaneous and sequential bilingualism. Simultaneous bilingualism refers to children who learn two languages from birth. One advantage here is that children often become fluent in both languages together, developing parallel linguistic systems that support each other.

Sequential bilingualism, on the other hand, describes individuals who learn a second language after establishing their first. A key benefit is that the first language is usually well developed, which can support second language learning. However, pronunciation and grammar in the second language may not be as “correct,” and learners may carry over structures from their first language. This isn’t a flaw; it’s part of the fascinating process of language acquisition.

Contrary to popular belief, bilingualism is not rare. In fact, monolingualism is the exception globally. In Wales, recent statistics show that more children report speaking Welsh than adults, reflecting the success of early years initiatives and Welsh-medium education. This generational shift is encouraging and highlights the importance of nurturing bilingualism from a young age.

But bilingualism is more than just speaking two languages; it’s a cognitive and creative asset. Bilingual children often show enhanced creative thinking. They might invent imaginative stories that blend cultural elements from both languages or use objects in unconventional ways during play, such as turning a spoon into a microphone. This kind of divergent thinking is a hallmark of creativity.

They also develop a strong understanding of word concepts. Knowing that a dog can be called “dog” in English and “ci” in Welsh strengthens their grasp of symbolic representation. They’re often quicker to understand abstract categories like “emotion” or “furniture” because they’ve encountered these ideas in multiple linguistic contexts.

In terms of curriculum achievement, bilingual children frequently excel in subjects like maths and science due to their cognitive flexibility. They perform well in literacy tasks, especially when both languages support academic vocabulary. Their ability to switch between languages and tasks contributes to greater adaptability, helping them adjust to new classroom routines or environments with ease.

Another fascinating aspect is communication sensitivity. Bilingual children often adjust their language depending on who they’re speaking to, Welsh with a grandparent, English with a teacher. They’re more attuned to tone, gesture, and context, which enhances their social awareness and empathy.

When it comes to problem-solving, bilinguals often approach challenges from multiple angles. Whether building a block tower or resolving conflict during play, they show persistence and creativity. Their brains adapt to frequent use of language, much like muscles grow with exercise. Studies show increased grey matter density in bilinguals, especially in areas linked to language learning and executive function.

Bilingual children tend to switch between play narratives easily, adapting quickly to new rules or routines. Their executive function is often stronger, helping them wait their turn, ignore distractions, and follow multi-step instructions. They also develop broader conceptual networks. A bilingual child might associate the word “water” with “rain,” “bath,” “drink,” and “river” across both languages, showing rich semantic connections. Their metalinguistic awareness is impressive; they might ask, “Why do we say ‘an apple’ but ‘a banana’?” or play with rhymes and puns in both languages.

Culturally, bilingual children often show perspective-taking. They understand different norms and traditions, and their storytelling may include characters from diverse backgrounds. In design and technology (DT) and play, bilingualism encourages idea generation, reduces fear of failure, and supports iteration and flexibility. A child might build a bridge, knock it down, and rebuild it differently—demonstrating trial and error and creative problem-solving.

They also show improved phonetic awareness, noticing subtle differences in sounds across languages. Their expanded vocabulary allows for more descriptive language, and they often understand synonyms and antonyms more easily. In reading, they demonstrate strong comprehension, inferring meaning from context and asking deeper questions about stories.

Importantly, bilingual children can transfer literacy skills between languages. A child who learns to segment sounds in Welsh may apply that skill when reading English words. They might use storytelling structures learned in one language to write or retell stories in another.

And yes, code-switching happens. Some see it as a problem, but I see it as a sign of linguistic agility. Whether it’s Wenglish or a blend of Welsh and English in play, it reflects a child’s ability to navigate complex linguistic environments with ease.

Further Information

Lowri Thomas

Principal Communications and PR Officer

Corporate Communications and PR

Email: lowri.thomas@uwtsd.ac.uk

Phone: 07449 998476